Important Dates

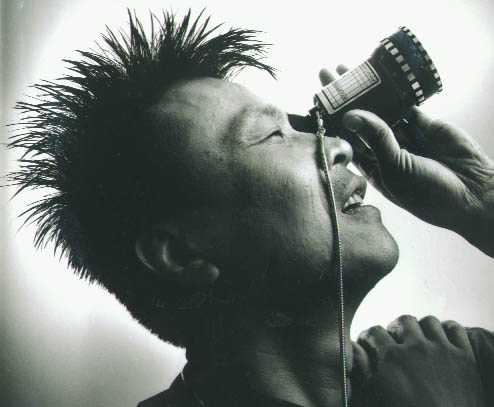

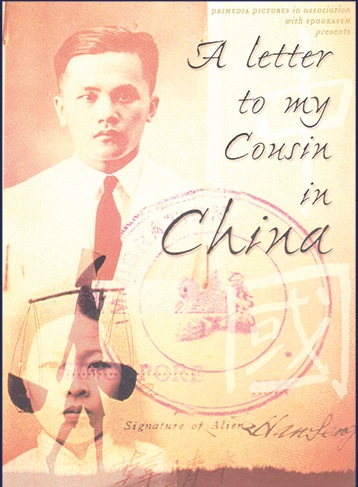

Screening of the documentary "A Letter to my Cousin in China" by Henian Han

2021-07-05 18:00 to 20:00

Online via Zoom

SYNOPSIS

"Perhaps home is not where you live but how you live.."

A LETTER TO MY COUSIN IN CHINA is an intensely personal and deeply moving account of one family’s history. It is the universal immigrant’s story about a lifelong search for home, and one man’s personal realization of what home means to him. A LETTER TO MY COUSIN IN CHINA is a documentary, 20 years in the making.

The story begins with the extraordinary events of Henion Han’s parents’ early lives, documenting their childhood in Hainan Island (off the Southern Coast of Mainland China) their arranged marriage and tragic separation, to their poignant reunion in South Africa 14 years later.

It tells of a family’s struggle to forge an identity and find a home in a strange and foreign land, following the life of the small Chinese community living in a shadowy demi-monde, neither black nor white, in a society where those colors counted for everything.

Giving an inside view of what it was like to live as a second class citizen during the apartheid years. From Hainan Island to South Africa, from Taiwan to America, A LETTER TO MY COUSIN IN CHINA follows the life of the filmmaker’s dying father as he prepares for the afterlife.

About the Production

A LETTER TO MY COUSIN IN CHINA is the story of the family of Henion Han, a South African filmmaker and photographer. The story begins with the extraordinary events of his father and mother’s early lives – his father’s childhood in Hainan Island, his arranged marriage, the young newlyweds’ separation after only three months together – which was to last 14 years – the astonishing circumstances that led him to board a ship that landed in Durban and his stay in South Africa for the next 40 years. As the story unfolds, we begin to see and understand a little more about the impetus and the effects of the Chinese diaspora over the course of this century.

It is also about the second central character in Henion’s life, his mother, who lay buried in the mountainside in Taiwan. She was an only child who came from middle peasant stock. Henion’s mother, like so many other girls of her class and standing, never learned to read or write. During the Japanese invasion of Hainan, she fled to Singapore, where she lived for many years as a poor and homeless refugee. These circumstances made it very difficult for her husband to trace her whereabouts.

“My parents were separated for 14 years, neither knowing the whereabouts of the other,” recounts Henion. “Then, during the last year of the war, my father was in Durban, where the ship he worked on was being repaired after being hit by a Japanese submarine. By chance he was offered a clerical job with the Consulate of the Chinese Nationalist Government in Johannesburg. After the war, through letters to distant friends and relatives, my father managed to trace my mother and pay for her to join him.”

“During the passage by ship to South Africa my mother suffered a severe mental breakdown. On arrival in Johannesburg she was admitted to hospital, where she was bedridden for a year. After her recovery she gave birth to six children in the course of seven years. I was the fourth, and the first male – to my father’s delight and my mother’s pain..”

“We spoke a unique Hainanese dialect at home. There were only two other families in the whole of Africa who spoke the dialect. This isolated my mother even more, not being able to communicate with other Chinese people.”

In 1967, after 20 years in Johannesburg, Henion’s father was transferred to Taiwan, “My father felt this was potentially an opportunity for us to find a real home and leave behind our lives in apartheid South Africa. In the first week we arrived in Taiwan, 19 years after her first mental collapse, my mother suffered a relapse of what was diagnosed as manic depression. She remained bedridden for three years whilst we stayed in Taipei. My father realized that this would not be our home after all.

“When we returned to South Africa we went back to Troyeville and lived in the same street where we grew up. Despite us believing and hoping, my mother never fully recovered. When my father retired, he went to prepare his and my mother’s burial site in Taiwan. He commissioned a stone carver to build a tombstone for them to lie alongside each other in death. He would have preferred to have the tombstone in Hainan, but politics prevented it. China at that time was off-limits to most people, especially those working for the Taiwanese government. When my mother died in 1983 in Johannesburg, my father went to Taiwan a third time, to bury her..”

In 1990- Henion accompanied his father to visit his birthplace in Hainan Island for the first time in more than 50 years. During that visit his father realized that despite his dreams, he could not go back and live in his original home. Too much had changed. The old man decided to stay with his daughters and grandchildren in America. In 1997 he was diagnosed with cancer. He decided then to have his wife and his mother exhumed and cremated so that they could be buried alongside him in the USA. Three weeks after completing this last pilgrimage – the emotional climax of the film – Henion’s father “had a glass of whiskey, lay down, and died.”

“Isn’t it ironic”, Henion muses, “that my mother and grandmother are buried in the USA – a place they have never been to before? I look at myself and ask – what is home.. Where is home? I am Chinese, and yet I am not. I do not speak Chinese fluently, let alone read and write it, but my past, my roots is not something I can simply ignore. And my children – what are they, half-white, half-Chinese? Nationality and patriotism seem meaningless in this context. Perhaps home is not where you live but how you live?

- To find the flyer of this event, please click here.